Summary

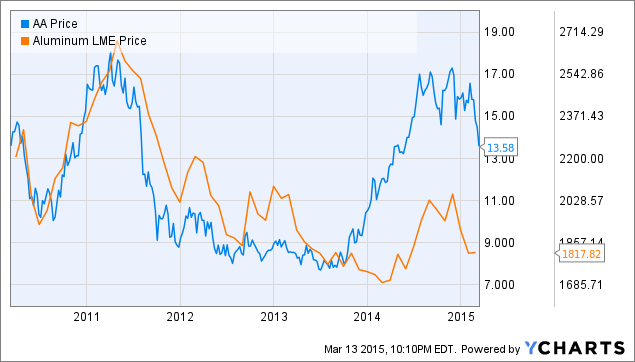

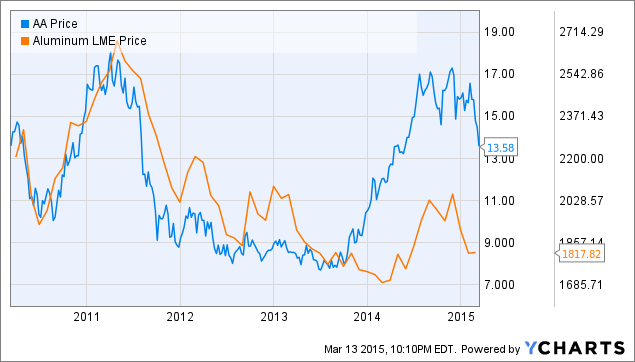

- For the last 5+ years, shares of Alcoa have, for the most part, tracked the LME aluminum spot price.

- A change in internal investment strategy could be freeing the company from the clutches of the commodity.

- After three acquisitions, Alcoa can produce almost every part required in a metallic airplane.

- The recent acquisitions have also beefed up Alcoa's exposure to titanium at a crucial time.

For as long as I have been trading stocks, there has been one thing drilled into my head over and over again when it comes to companies in the commodity business: their stock almost always trades with the commodity itself. Whether it be gold, copper, natural gas, oil, or any other commodity, this rule always holds true. Don't believe me? Just check any oil stock's performance since the price of the liquid began its decent in late November.

The thought behind this principle is so simple that even the most inexperienced of investors should be able to understand. When companies produce a commodity and the price of that commodity is high, revenue is equally high, margins expand and earnings rise. On the other hand, when the value of the underlying commodity falls, revenue dips, but costs remain the same. Therefore, margins contract (maybe even turn negative) and earnings decline sharply. In each case, the stock trades accordingly, as can be seen in the 5-year chart of the aluminum producer, Alcoa (NYSE:AA), presented below.

AA data by YCharts

So, what can a company do to break this lockstep correlation from occurring? The company must fundamentally change its business. And that is exactly what Alcoa has been doing ever since Klaus Kleinfeld took the helm in 2008, divesting high cost production capacity and investing in new value-adding technologies through both internal development and external acquisitions.

When Kleinfeld took over, Alcoa was coming off one of the strongest years of financial performance in memory. Revenue reached a record $30.7 billion and EPS was reported at $2.95. Now, just as Alcoa appears to be returning to form, recently reporting what were undoubtedly the strongest yearly financial results at the company since 2007/2008 that generated earnings of $.92 per share on $23.9 billion in revenue, some are beginning to call a top. Some of the bearish theses include an oversupply of aluminum or a slowdown in aluminum demand. Both of which are health concerns. However, investors must realize that this Alcoa is not the company that saw its shares decline some 80 plus percent in 2008.

For starters, the old Alcoa was investing heavily in expanding the company's production capacity. Read the following excerpts from the 2007 annual report:

We invested in new plants, expanded production at others, modernized operations, renegotiated long-term power agreements, and built new energy facilities to extend our energy access at competitive rates, while also continuing to invest in growth markets such as Brazil, China, and Russia.

In total, our capital investments were approximately $3.16 billion in 2007 (excluding currency impacts) with nearly 60 percent, or $1.7 billion, dedicated to growth projects.

The "growth projects" talked about referenced the construction of two smelters in Iceland and Norway, while much of the rest of the capital budget was spent on various energy producing projects and other, smaller capacity building initiatives. Each of these investments caused the company to become more levered to commodity pricing. Thus, when the LME price sank in 2008, you better believe the stock followed.

By contrast, the new Alcoa has targeted its investing activities on the downstream, value-added side of the business, while divesting high cost capacity to lower its positions on both the alumina and aluminum cost curves.

Above is a graphical representation of Alcoa's positioning on the aluminumcost curve. As you can see, the company has successfully reduced its positioning by 8% points over the last four years through the closing of high cost capacity, something that was not occurring at the peak in 2008. The same holds true for the company's position on the alumina cost curve shown below.

The change here has been a bit more modest, declining only 5% pts over the four-year span. However, in both cases, Alcoa is improving its positioning, thus protecting itself from the volatile swings that can be seen in the commodity market by shutting down high cost capacity. Since the peak in 2007, the company has closed, curtailed, or sold roughly 31% of its highest cost smelting capacity. And Alcoa appears poised to expand upon these efforts in 2015, announcing the review of 500 metric tons (14%) of smelting capacity and 2.8 million metric tons (16%) of refining capacity for curtailment or divestiture.

Moving to the perhaps more exciting side of the portfolio transformation, Alcoa has begun to differentiate its products for more sustainable end markets such as aerospace and automotive. In aerospace, the strides made have been phenomenal, adding Firth Rixon, Tital, and RTI International to its portfolio in the past 6 months or so. Each of which, has allowed Alcoa to expand its presence in the aircraft. Just look at the graphic below.

Alcoa now has the ability to produce nearly every part of the metallic-intensive aircrafts assembled and sold by the likes of Boeing (NYSE:BA) and Airbus. These differentiated products are much less likely to be exposed to the same commodity-based pricing scrutiny as the basic aluminum or alumina that was being produced back in 2007.

The acquisitions of these three companies also makes Alcoa one of, if not, the top producers of titanium domestically. This shift could not have come at a better time, as Russian sanctions are currently threatening the titanium imports that U.S. industries, as well as the defense sector, so heavily rely on.

Final Thoughts

Summing it all up, Klaus Kleinfeld is truly transforming Alcoa as we know it, attempting to break both the company and the stock free from their cyclical ties to the commodity price of aluminum. And, I believe he is doing an excellent job of it, targeting the company's investment spending on value-enhancing, downstream initiatives instead of on the expansion of high cost capacity that was seen in 2007. Though the prices paid for these acquisitions do include a fairly sizeable premium, the investments are justified from my standpoint and the stock should come to reflect that soon enough.